At the heart of Muktabodha’s mission to protect and preserve India’s great spiritual legacy lies its Digital Library, a freely accessible resource for scholars and laypersons around the world.

By the end of this year, this Digital Library will transfer to a new archiving platform and the first collections to migrate from the current to this new platform will be the Gokarna texts. This collection consists of 235 unique Vedic texts, that were collected over generations by priestly families living in the temple town of Gokarna on the south-west coast of Karnataka in India. It includes several important texts and images on rituals from the Yajur Veda school.

Around 2004, in an historic move, three Brahmin families from Gokarna decided to digitize their treasured collections of Vedic texts. According to Dr. Borayin Larios, Assistant Professor at the Department of South Asian, Tibetan and Buddhist Studies, University of Vienna, Austria, the heads of the Joglekar, Kodlekere, and Samba Dixita families come from a tradition of Kṛṣṇayajurvedic teachers and Sanskrit pandits of a living lineage, and for generations they have carefully preserved their collections of texts from the Aśvalāyana and Baudhāyana Śrauta traditions.

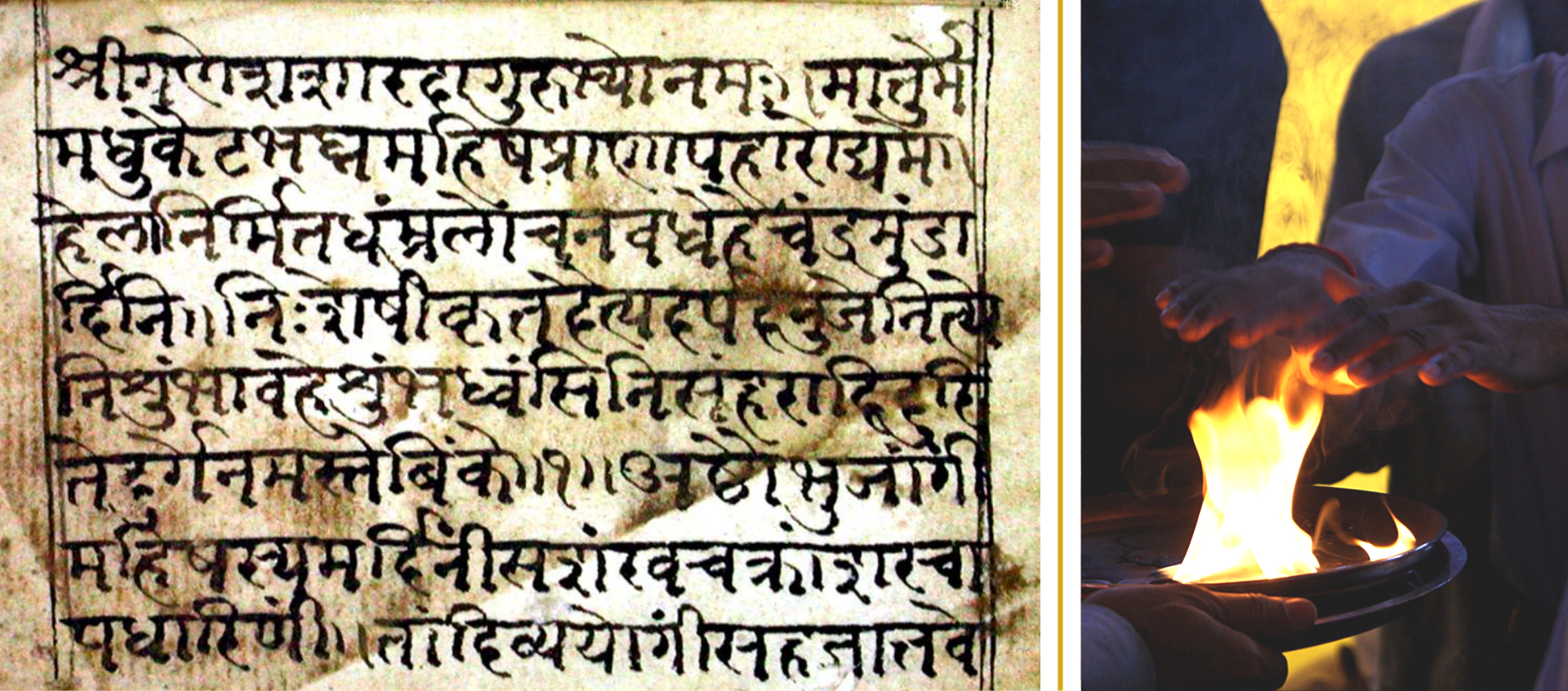

Dr. Larios, who is also a member of Muktabodha’s Academic Advisory Council, explains that the texts are central to their priestly calling, and used as manuals for ritual, reference, and teaching. The hand-written manuscripts, however, are no substitute for the extraordinary memorization required of learned practitioners of the oral traditions of the Vedas. Indeed, the texts come alive during the Vedic ceremonies, whenever they are performed across India today. Not only have these families been performing Śrauta rituals for generations, particularly Darśapūrṇamāsa Iṣṭis and Somayāgas, but they also see preserving this knowledge they hold, both in memory and in their most treasured manuscripts, as their highest duty.

Most of these paper manuscripts are 100-150 years old and in remarkably good condition. Using traditional methods of preservation, the paper on which they were written was first dipped in an alum solution and then dried, thus rendering it distasteful to insects, rodents and fungus. The black ink used was indelible, and the manuscripts were tied together tightly in cotton cloth that had been soaked in turmeric water, which not only imparted an auspicious colour, but also infused it with anti-microbial qualities. In addition to careful storage and handling, the manuscripts were brought out each year during Svātī nakṣatra, when the sun’s rays are believed to contain special anti-microbial qualities. Each manuscript bundle was unwrapped, dusted, and checked for insects, before being placed in the open to be bathed in sunlight.

Local priests with beautiful penmanship worked with the families to ensure absolute accuracy in the transcription. Some manuscripts also include watercolour illustrations and decorated title pages, but little is known about who added these delicate touches.

Contemporary challenges surrounding the preservation of these precious texts for posterity became a serious concern, particularly since their value was not fully appreciated beyond the members of this shrinking community. A chance meeting with members of the Muktabodha Indological Research Institute at the performance of a rare Somayāga provided the answer, and, in 2003, Muktabodha's photographic team was invited to digitally photograph the entire collection.

Mindful about protecting from potential misuse the knowledge contained in these manuscripts, the families deliberated extensively on the implications of making them freely available on Muktabodha’s Digital Library. Ultimately, however, they decided that the potential good from offering these texts to current and future students and practitioners of the Vedas far outweighed any dangers of misuse. So, in the spirit of vidyādāna, the gift of knowledge, they agreed to share their sacred texts digitally with those who study and value Vedic knowledge.